Luke Skywalker

Super Moderator

{vb:raw ozzmodz_postquote}:

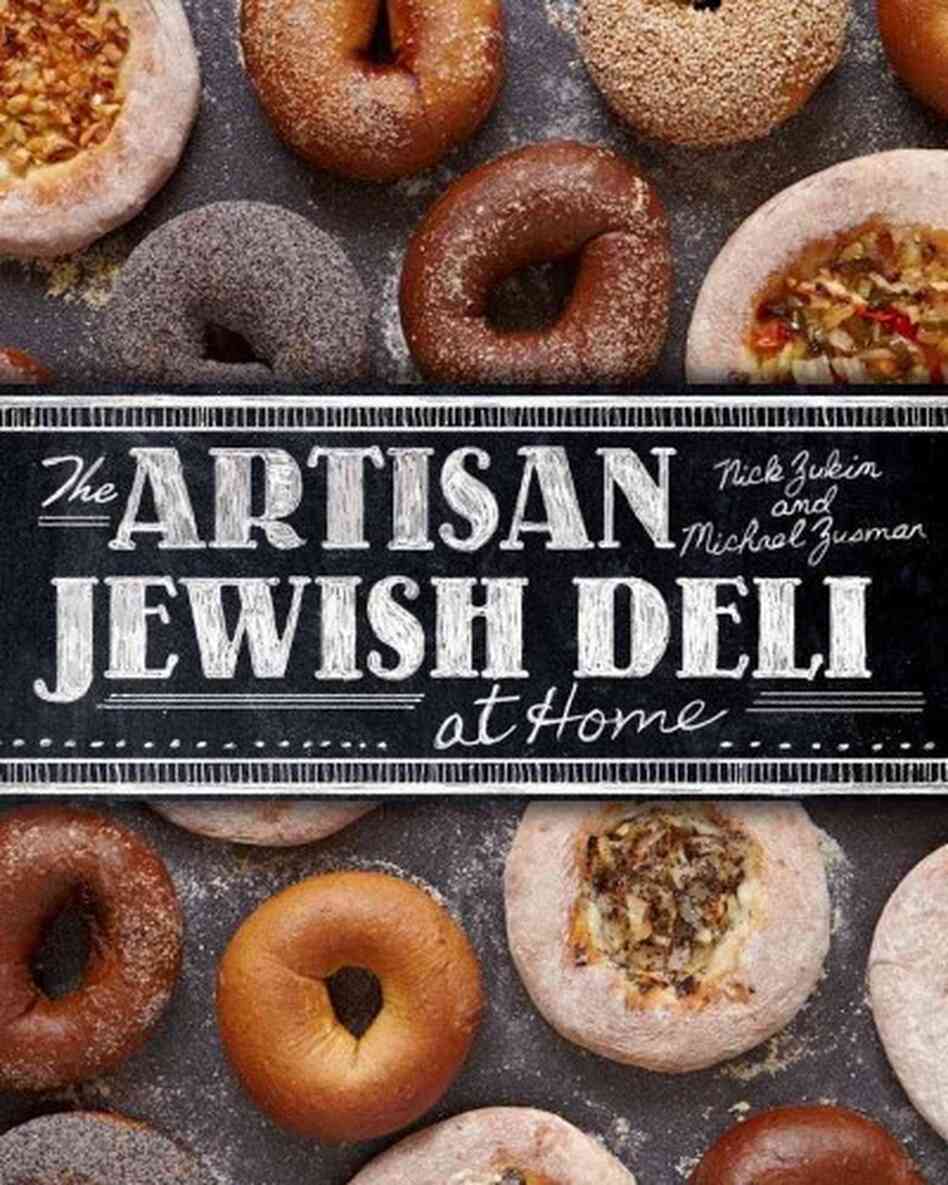

[h=6]The Artisan Jewish Deli At Home[/h] by Michael C. Zusman and Nick Zukin

Hardcover, 254 pages | purchase

There are two important things that you learn about Michael Zusman, baker and co-author of The Artisan Jewish Deli at Home, when you bake with him.

First, his real job has nothing to do with bread or writing recipes. He's a trial judge. "Full time," Zusman says. "Wear a black robe every day."

Zusman presides from the bench in Portland, Ore. He handles drug cases, small claims disputes over shoddy car repairs, fights between landlords and tenants, and other daily battles that overload America's legal system. But he had a few days off, and visited Washington, D.C. And Judge Zusman made some of the best bialys I've ever had, right in my own kitchen.

In case you've never had a bialy, it looks like a miniature pizza, topped with roasted onions and poppy seeds. Bagels are far more famous in the annals of eastern European Jewish cooking, but plenty of people feel passionate about bialys. They got their name as a favorite food in Bialystak, a major city in what's now Poland.

Zusman and his co-author's cookbook promises that if you follow their easy recipes, you can make your own bialys and pastrami and pickles – and bagels – better than you could buy at your local deli.

And as Zusman baked, and talked, his story reminded me about the redemptive powers of cooking.

Because here's the second thing I learned about Zusman: He stumbled into baking. And it helped save him.

As Zusman began telling his story, he was weighing out the ingredients for the dough — flour, yeast, sugar and salt. And water.

He says whenever you bake, it's better to weigh the ingredients than measure them — a scale is much more accurate. On the other hand, he says, baking's more forgiving than you might think. So don't feel boxed in by the rules.

"People feel so intimidated by baking and they shouldn't," Zusman says, turning on the mixer, equipped with a dough hook. "It's not a science experiment. It doesn't need to be quite that precise."

But back to Zusman's personal story: He spent more than 20 years working as a lawyer, specializing in suing financial companies. And he says his work literally started making him sick. He had trouble sleeping. His stomach was always churning. He was always leaping into battle.

Then one day, he discovered dough. "I had just quit drinking," Zusman says. "I was a pretty heavy drinker and had quit and had lots of time to fill. So, my ex-wife and a friend signed me up for a bread-baking class. Talk about a piece of dumb luck, I just ended up really finding something that I loved."

Zusman also discovered that he had, "go figure, an affinity for Jewish breads."

i i

hide captionJudge Michael Zusman's bialys are topped with roasted onions, poppy seeds and coarse salt.

Daniel Zwerdling/NPR

Judge Michael Zusman's bialys are topped with roasted onions, poppy seeds and coarse salt.

Daniel Zwerdling/NPR

When I sound surprised that Zusman graciously credits his ex-wife, he looks more surprised. "She's in the acknowledgements of the book, she did a very good proofread of the introduction," he says, sounding like a proud, well, husband. "We produced this fabulous daughter together and we get along real well. So..."

He pauses, peers into the mixing bowl and turns off the machine. "I'd say this dough is just the way it should be" – soft and smooth, with just a tiny tug on your fingers like you'd get from a sticky note.

In any case, learning how to bake was the first event that changed Zusman's life for the better. "I spent weekends experimenting with different kinds of breads," he says, as he starts chopping the onions. He wouldn't just make a couple loaves, he'd make a dozen and give them away to friends.

Then came the second change, seven years ago: State officials in Oregon made him a trial judge. And Zusman says he loves it. He loves not being the guy who leaps into battle anymore. Instead, he's the guy who brings resolution. "It's an opportunity to exercise compassion, and patience," Zusman says, "things that in my regular life I may not be fabulous at, but I get to practice every single day."

And Zusman says one of the most common ways he gets to practice compassion and patience is when people protest their parking tickets.

"When people feel they've been unjustly given a parking ticket, the emotions run higher than just about any court I've ever presided over. It's amazing," Zusman says. Especially when the meter expired only a couple minutes before they got the ticket. But, he adds, if you come to court and ask for leniency politely – or even if you write a letter of protest, and it's graciously worded and civil – then he may well slash your fine.

"I tend to be sympathetic to citizens," he says. "Yes, it's a technical violation, but it seems really unforgiving for the officers to follow the letter of the law."

[h=3]Book Reviews[/h] [h=3]From Kolbasa To Borscht, 'Soviet Cooking' Tells A Personal History[/h]

[h=3]Code Switch[/h] [h=3]Cooking In A Latin-Jewish Melting Pot[/h]

While I'm watching Zusman cut up the onion, I'm thinking about his life. And I tell him, the more you talk about being a judge, the more you sound like you're talking about baking. Be patient. Follow the rules, except, it's good sometimes to bend them. Be compassionate, and give most of your bread away.

Zusman looks at me like I'm nuts. "If those analogies exist, they're purely subconscious," he says. "But it actually makes sense. I'll go with that."

Next, Zusman arranges the chopped onions in the shape of a narrow log on a baking sheet, and he slides it into the oven – he roasts the onions until they're gently golden instead of sautéing them, which means no oil splattering on your stove.

Meanwhile, the dough is all puffed up, and looking proud and yeasty. Zusman punches it down, and forms little balls. His fingers coax and pull each one into a disc. Then he tops each one with the roasted onions and poppy seeds and coarse salt, and bakes them on top of parchment paper for 20 minutes.

And Judge Zusman's bialys are done. Brown, and crusty, and showered with onions and poppy seeds. Like confetti.

"Look at this," Zusman says, with his biggest smile all day. "I wish everybody could see this."

"These are beautiful," I murmur.

Zusman laughs. "If I do say so myself."