Luke Skywalker

Super Moderator

{vb:raw ozzmodz_postquote}:

NPR continues a series of conversations about The Race Card Project, where thousands of people have submitted their thoughts on race and cultural identity in six words. Every so often, NPR Host/Special Correspondent Michele Norris will dip into those six-word stories to explore issues surrounding race and cultural identity for Morning Edition.

Kate Byroade lives in Connecticut, but she has a family history that reaches far back to the American South. She always knew her ancestors had once owned slaves, but had been told again and again, particularly by her Southern grandmother, that the family's slaves had been treated well.

"She was matter-of-fact that the family had owned slaves in the past," Byroade says. "And emphasized that we did not come from 'plantation-type' families — that our slaves had been trusted house servants."

"At first this seemed OK to me because it was OK to her," Byroade continues. "But eventually I understood that the domination of another person's free will was unacceptable."

In 1844, an 8-year-old girl was purchased at a slave auction. The girl, named Harriet, served as a maid to Byroade's great-great-great-great-great-grandmother.

i i

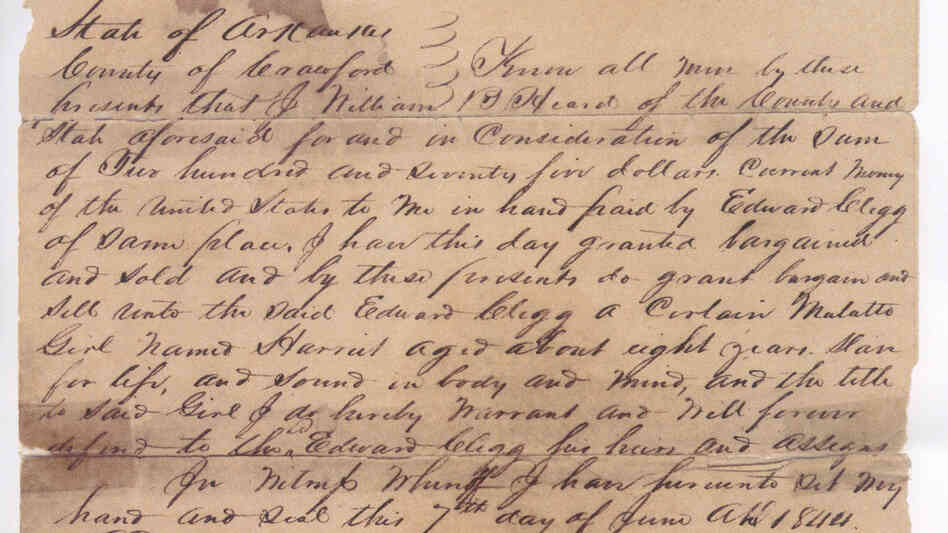

hide caption"I have this day granted bargained and sold and by these present do grant bargain and sell unto the said Edward Glegg a Certain Mulatto Girl named Harriet aged about eight years. Slave for life, and sound in body and mind, and the title to said Girl I do hereby warrant and will forever defend."

Courtesy of Todd Perry

"I have this day granted bargained and sold and by these present do grant bargain and sell unto the said Edward Glegg a Certain Mulatto Girl named Harriet aged about eight years. Slave for life, and sound in body and mind, and the title to said Girl I do hereby warrant and will forever defend."

Courtesy of Todd Perry

That realization eventually brought Byroade to her six-word submission to The Race Card Project: "Slavery's legacy broke my family pride."

The idea of the benevolent slave owner is a common one, and looking past that family lore was just one aspect of Byroade's long personal journey of discovery about race.

The link between Kate Byroade's ancestors and Harriet, the girl they once owned, was discovered by Byroade's distant cousin, Robert Clegg. He found Harriet's bill of sale and gave it to a librarian named Todd Perry, one of Harriet's descendents. You can read more about Clegg, Perry and Harriet here.

[h=3]The Race Card Project: Six-Word Essays[/h] [h=3]Discovering Grief And Freedom In A Family's History Of Slavery[/h]

"Even going back to her childhood, this is something that she's struggled with," Michele Norris tells Morning Edition's Steve Inskeep. "The things she saw in textbooks or the stories she saw on TV — shows like the miniseries Roots — didn't necessarily square with the genteel stories about slavery she heard at the family dinner table."

One childhood incident left a particular psychological mark on Byroade. When she was 10 years old, her class was tasked with an assignment about their immigrant ancestors.

"And I let drop that my family had owned slaves," Byroade recalls. "The school that I attended was probably about, at the time, 60 or 70 percent African-American. ... And I did not think that I was boasting."

On her way home from school that day, a group of black classmates and their older siblings went looking for her, Byroade says. "And those children ... decided that they had to chase me, and they had to scream at me, and they had to yell at me."

i i

hide captionKate Byroade knew her family members had owned slaves. But that knowledge became even more troubling for Byroade when she learned that an ancestor once owned an 8-year-old child.

Courtesy of Shedrick Robinson

Kate Byroade knew her family members had owned slaves. But that knowledge became even more troubling for Byroade when she learned that an ancestor once owned an 8-year-old child.

Courtesy of Shedrick Robinson

That episode stayed with Byroade, and deepened her interest in trying to understand this historical chasm in America — something that became even more complicated the more she learned about her own family's history.

A distant cousin discovered that when Byroade's great-great-great-great-great-grandmother arrived in the U.S. from Ireland in the 1800s, a black child immediately was purchased to serve as a handmaiden, Byroade says.

"And when she discovered that this child had been purchased ... slavery was not just this abstract idea," Norris says. "The history was then attached to a person. It wasn't just an abstraction."

The child's name was Harriet, and she "was a young child in the Indian Territory, scooped up by outlaws and used to cover a bet on a horse race," Byroade says.

Byroade takes pride in the fact that she has surrounded herself with all kinds of diversity. She lives in a diverse neighborhood, she attends a diverse church, and her kids belong to diverse Girl Scout troops. But her family pride isn't quite what it once was.

"I think you can feel pride in the legitimate accomplishments of your ancestors. But I don't think you can feel pride in the fact that they owned slaves," Byroade says. "I don't think you can feel pride that the wealth and prestige was accomplished on the backs of people who were not free, who had no say, who were subject to your whims.

"We are very shy in this culture about calling out the great wickedness of slavery, and we should not be," she says. "We must not be."