Luke Skywalker

Super Moderator

{vb:raw ozzmodz_postquote}:

St. Louis had a Greyhound Bus Terminal in 1984, not a Trailways. Felix Vail told Tulsa, Okla., police investigating Annette Vail's disappearance that he dropped her off at the Trailways in St. Louis.(Photo: Courtesy of Missouri History Museum Library and Research Center)

Felix Vail answered his door to see Detective Dennis Davis and another officer from the Tulsa Police Department. It was Jan. 22, 1985, and he had been expecting them.

Weeks earlier, he had dropped off a photograph of Annette at Davis’ request. Two weeks before that, Vail had filed for divorce, citing an inability to find her after a “diligent search.”

GONE: Read the full Felix Vail saga

Vail invited the officers in, and they chatted for more than two hours — more about him than the missing woman.

Davis said her mother, Mary Rose, mentioned her daughter had received more than $90,000 from her father’s estate.

Vail confirmed that was true, saying the couple had spent much of that money traveling in foreign countries. He said they kept their money in cash because they didn’t trust banks. In fact, he said he had found about $10,000 in cash when he returned home.

The next day, Vail telephoned a lawyer, who promised to talk with the officers, telling them to “leave me alone,” he wrote in his journal.

When Davis returned five days later, Vail had a detailed alibi: The couple left Tulsa between noon and 3 p.m. Sept. 13, 1984, and stayed the night in a hotel in Claremont, Oklahoma. After two nights of camping on the river, Annette awoke and told Vail she had decided to leave him. He took her to the Trailways Bus Station in St. Louis and left before she bought the ticket.

He told the officers she told him she was headed for Denver, where she planned to get a fake ID card and leave for Mexico.

They asked Vail if he would take a lie detector test. He said no.

After the officers left, Vail wrote in his journals about Annette’s mother: “Mary making Davis dance, and he’s trying to make me dance.”

Vail claimed Annette had bought a gun. “I regret some not letting Annette kill her when she wanted to & Annette is free of her (at least as long as she stays incommunicado).”

He wondered what to do about Rose. “Now how do I get free of her short of giving her the property?” he asked in his journal. “One way (that I don’t know how to do) is prove to Davis she is manipulative old whore who’s [sic] motivation is accusing me (of whatever) is mostly money and very little if any parental concern for Annette.”

He fired off a letter to Rose. He blamed her for the “bad things” in Annette, saying she had “stymied the love between us to the point where we both decided that she could get more ... from miscellaneous emotionally and sexually hungry men than she was getting from me.”

He wrote that after the couple came back from Costa Rica, Annette “began seeing friends and relatives ... and doing what she called completing her relationships with them for the purpose of getting ready to drop everybody and start over.”

He wrote that she “disappeared herself from you because she realized that you probably would never voluntarily stop reenergizing in her and superimposing on her the same value system you live by that makes her see you and your mother (and herself partially) as zero self image whores for approval in the form of male attention as prerequisite to the periodic and temporary permission to feel good about yourselves.”

Vail explained that the two left each other “with no plans to communicate in the future … I have not the slightest idea where she might have gotten to by now. I will tell you that I love the spirit part and very much respect her right to freedom and so I also assure you that even if I did know, I would not tell you.”

To Rose, his response felt like a cold slap in the face. She could feel police interest in her daughter’s disappearance growing cold, too. Perhaps they would be less skeptical if she talked to them in person.

She decided to return to Tulsa in April 1985 and sent Vail a note that she would be in town.

“Dear Mary, I would like to see you to [sic],” he wrote back. “I think it could be more than lovely to be with you some. I look forward to it. Love, Felix.”

When she arrived, she was unable to reach him and grew worried about her daughter.

Annette (left) and Mary Craver, circa 1977-1978<span style="color: Red;">*</span>(Photo: Special to The Clarion-Ledger)

She decided to slip inside the rental cottage she once owned, discovering that all of Annette’s clothes were gone. So were all but a few of her possessions, including the diary she kept.

Inside a Barbie suitcase, Rose found a photograph of her daughter and several of her identification cards. She also located things that Annette had written, including a Feb. 17, 1984, note that contradicted Vail’s claim that the couple had spent most of her inheritance on their travel to Mexico and Central American countries.

Instead, the note detailed how they used the money to buy the Fiat, pay off all of Vail’s loans, and deposit $36,000 into Louisiana Savings. “As of today, we have $41,600 in cash.”

Rose shared the information with police.

Detective Davis visited Vail again, “acting like Columbo with two more questions,” he wrote in his journal.

Vail had told Davis before that he and Annette kept all their money in cash.

Now he acknowledged to Davis that they broke the money into smaller cashier’s checks.

After a while, the detective left. Vail hoped the answers satisfied him.

Vail dreamed about Annette in bed “with this great big ugly fat guy,” he wrote in his journal. “She was feeling dumb and ridiculous for having let him into her and being at the same time as high as she could be on having just fled the ego the energy of his desire and attention and all the self validation that would be milked from it.”

Vail never heard again from Davis, who closed the missing person’s case.

Unable to talk with Vail in person, Rose persisted in telephoning him. She tried him at home in Tulsa. She tried him at his parents’ home in Mississippi.

On Sept. 14, 1985, she finally reached him in Tulsa. When she asked about Annette’s missing clothes, he told her he had given all of them to charity.

Rose asked about Annette’s whereabouts, and Vail refused to say where she was.

She mentioned that she was talking to police. When she pressed for more details about what had happened to the nearly $100,000 that Annette inherited, she said Vail shot back, “That’s all you really care about — her money.”

She hung up.

- <span style="color: Red;">*</span>

Each day in his journals, Vail noted his encounters with women. He hopped from bed to bed, sometimes in the same night. When the sex was good, he described it as “electric” and “mutually orgasmic.” When he was unable to have sex with a woman, he blamed it on her “fat.”

When problems arose in the relationships, he blamed their egos, never his own.

December came, and temperatures dipped below freezing. Vail watched television, “vibrating on commercials.”

He thought about Annette. He had told Tulsa police she was schizophrenic and suicidal. Now he wrote that everyone he had met older than 2 years was “schizo.”

Less than two weeks before Christmas, he stepped out into the snow at 1 a.m. After watching the movie,<span style="color: Red;">*</span>The Hotel New Hampshire, he returned to the icy white, this time in his bare feet. “It’s coming down in bigger flakes now & around 2 inches, it is magic to walk & frolic in it falling & fallen, clothes on & clothes off.”

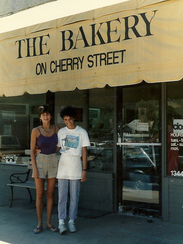

Disappointed with the private investigators' work into her daughter's 1984 disappearance, Mary Rose decides to return to her old job as a manager at The Bakery on Cherry Street in Tulsa, Oklahoma.<span style="color: Red;">*</span>(Photo: Special to The Clarion-Ledger.)

Fed up with the lack of progress in her daughter’s disappearance, Rose returned in 1987 to Tulsa, where she began working at her old job as a manager for the Bakery on Cherry Street.

She spent thousands on private investigators. When they were unable to locate Vail, she decided to look for him herself.

Tipped off that he was at someone’s house, she went there with a friend and found him sitting.

“So where did Annette go?” she asked.

“Mexico.”

“Where in Mexico did she go?”

He told her that he and Annette had made a pact they would contact each other after five years.

He never looked up, never stood up and never looked her in the eye.

She shook her head in disbelief and walked away. She didn’t believe a word.

- <span style="color: Red;">*</span>

Vail became fast friends with Tulsa native Scott Porter, an expert in martial arts who held more than one black belt.

Vail believed he was a martial arts expert, too, after practicing flying kicks into a mattress.

Each morning, he and Porter worked out, lifting weights together before hitting a Chinese buffet.

Over lunch, Vail shared that he had never felt bound by society’s rules, Porter recalled. “He dropped his silverware and began eating with his hands like a caveman.”

Some nights, the pair visited strip clubs in Tulsa, where Vail tucked dollar bills in the strippers’ panties. “Tulsa had more churches than gas stations,” Porter said, “but also more strip clubs than anywhere else I’ve lived.”

The pair also played pool and drank reduced alcohol beer.

Back home, Vail listened as Porter occasionally shared songs he had written, still dreaming of a career in music.

The two men reminisced about the women missing from their lives.

Those women linked them. Vail, at 45, had been married to Annette, just 18, and Porter, at 28, had dated Rose, who was 36.

Porter had driven Rose to her new home in California and returned alone. “My heart was absolutely broken,” he recalled. “We had a lot of good times. She needed to move on, and I didn’t.”

Not long after Annette vanished, Rose telephoned Porter and shared her suspicions that Vail had something to do with her daughter’s disappearance.

Porter began examining each word his friend spoke.

While Porter<span style="color: Red;">*</span>discussed his hopes of reuniting with Rose, he noticed Vail never mentioned that possibility with Annette.

One night, Vail seemed more open, he said. “He was crying like a baby, angry it didn’t work out differently.”

Vail explained that Annette “wanted to ‘recreate’ herself and that she didn’t want any contact with any portion of her past life. She wanted to totally break with herself.”

While Vail talked of breaking with the past, Porter was busy searching for his.

He had been adopted and decided to move to Minnesota to reconnect with his birth parents. While there, he met his future wife, Jennie.

Returning to Tulsa from Minnesota with a small son and another on the way, he renewed his friendship with Vail, who was so kind he later watched the boys while the couple went out on dates.

Once, during a discussion of fidelity, Porter said Vail shared that he felt “nobody could ever be faithful to one person.”

Months later, Vail “starts hitting on my wife,” Porter said.

Upset about this, he took Vail on a walk and confronted him.

Vail denied it all, Porter recalled. “He said, ‘No, no, she was hitting on me.’ ”

As they crossed the Arkansas River Bridge, a thought ran through his head — a thought he didn’t act on. “I was wanting to throw Felix off and wondering if I’d get away with it.”

Vail began dating Beth Field. She was attracted to his intelligence, and the pair grew close.

Then he began to call her a “whore,” and during a December 1987 argument, he became so violent that he ruptured her eardrum, according to court records.

She told Vail there was no justification for physical violence, and she said he replied, “If you quit behaving like a whore, I’ll quit hitting you.”

She discussed the issue with a therapist, she said. “I finally told this woman, ‘It’s all very nice, but one of us is going to be dead before this works.’ ”

Field took the advice of a close friend and attended an intensive 10-day meditation course in August 1988 on Colorado’s Western Slope. To her surprise, Vail came, too.

After the course, she received a telephone call from Rose, sharing details about the disappearance of her daughter, Annette.

After that conversation, Field said she evaluated the situation. “Each time I was with Felix, it was with the full awareness of not just the possibility, but the probability that he had taken Annette’s life.”

When the subject of Annette’s disappearance arose, Vail said he had been camping with her and that she decided she wanted to get away from her mother and that he had helped her set up an opportunity for her to change her name and move on, Field recalled.

Whenever she asked Vail about the disappearance, he denied involvement, she said. “Then one time he said, ‘What if I said yes?’ ”

Four months after the meditation course, Vail entered her home unannounced. Already drunk, he accused her of “imagined promiscuity,” according to the court order.

He slapped her, hit her and threw her across the bedroom.

“Will I get out alive?” she asked.

“It depends on what you tell me,” Vail replied.

The judge gave her a protective order, requiring Vail to keep his distance. Two weeks later, the sheriff reported that Vail was nowhere to be found.

Field said she felt caught in a “sick, addictive relationship, and it took quite some time to fully unravel it.”

Over time, her inordinate attachment to him began to fade.

While Field was visiting a meditation center in Texas in 1990, Vail verbally accosted her, and she felt the same anger and defensiveness rising up as before, she said.

She walked away to compose herself, and when she returned, she sat down next to him. “I told him, ‘There is a part of you that goes off, and it’s sick and it’s dangerous.’ ”

She said he looked at her and asked, “Really?”

“Yes, really.”

This time, the message seemed to soak in.

Vail left the course site the next day, and with a single exception about five years later, she did not see him again.

Contact Jerry Mitchell at<span style="color: Red;">*</span>[email protected]<span style="color: Red;">*</span>or<span style="color: Red;">*</span>601-961-7064. Follow him on Facebook

Powered By WizardRSS.com | Full Text RSS Feed